Opinion piece by Carl Hunter, OBE

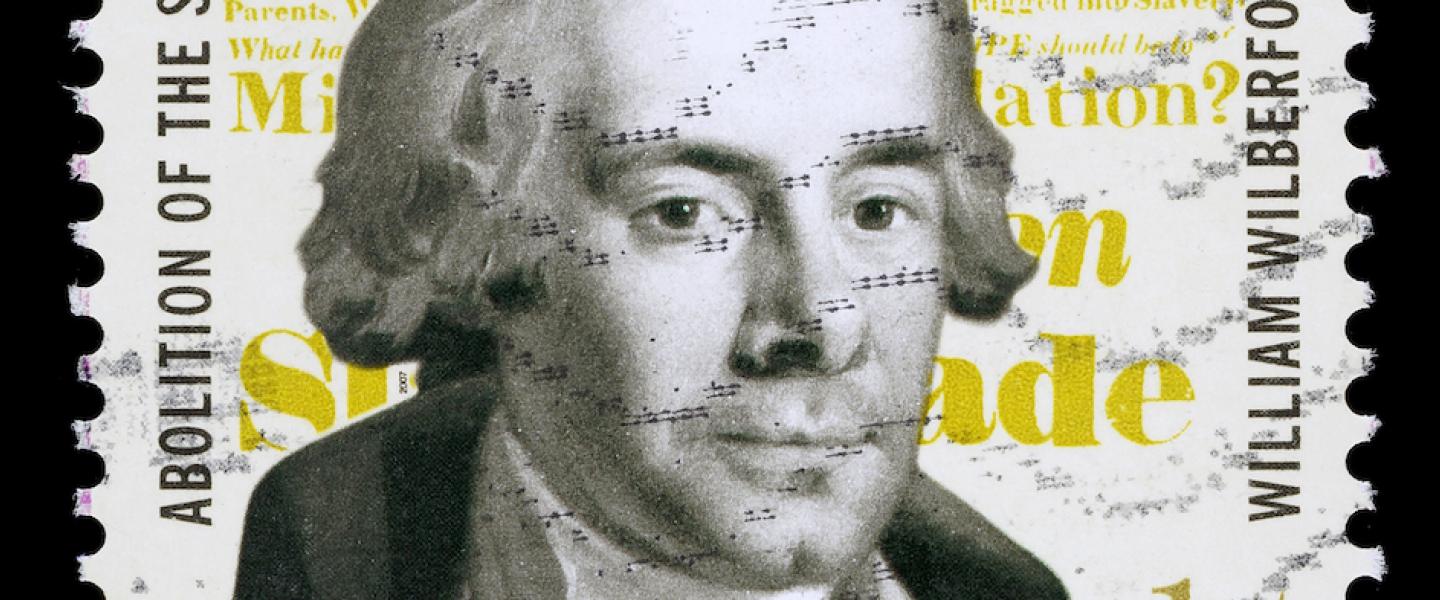

Rule of law is a distinguishing British value. It provides the greatest equal opportunity since everyone, including our Monarch, are equal before it. We may be proud of the work of an Englishman, William Wilberforce, who worked for 30 years to secure the UK’s Abolition of Slavery Acts in the early 19th century, and of the work of the Royal Navy, who took it upon themselves to eradicate its ghastly trade from the world’s oceans. We can also be proud of the United Kingdom’s “Global Force for Good” objectives, contained in the UK’s Integrated Review of Foreign Policy 2021, the Bribery Act of 2010, the Modern Slavery Act of 2015, and the British Government’s commitment to the Eradication of Modern Slavery at Sea in Maritime 2050: Navigating the Future, the UK’s first 30 year maritime strategy in 500 years. But why must we wait the 10-15 years that it states it will take to implement its just, optimistic and humane policy of eradicating modern slavery at sea?

Modern slavery may be defined as the severe exploitation of people for commercial gain. At a time of our greatest prosperity, why are the worst operators in our global shipping industry still employing people in a state of modern slavery on its worst ships? How have we arrived at the point we have in shipping where some of the ships that enable global trade are crewed by some of the cheapest labour on earth recruited 400 miles from a coastline and being employed in a state of modern slavery on some very poorly-run ships too.

In the way we crew our vessels, some of global shipping’s worst operators think that the cheapest crew is best. And some think that they should be worse than that. To allow mariners to exist in the state of modern slavery that they do is the opposite of good leadership and humanity, which is why in Maritime 2050, the UK Government committed to eradicate it.

It offers the prospect of the UK being the first nation on earth that both abolished slavery in the 19th century and eradicated its modern form at sea today in the 21st – that is an act of leadership. Shipping is global, and the United Kingdom has an opportunity to fulfil its “Global Force for Good” objectives by liberating the world’s oceans from modern slavery now, by working with the International Maritime Organisation to ensure that the world’s maritime nations vote for its eradication.

The UK legislated for its land-based equivalent in the Modern Slavery Act of 2015. This provides a very helpful text which can be used in its eradication at sea. It might be dealt with at the IMO by an amendment to the International Safety Management (ISM) Code. This provides our international maritime standard for the safe management and operation of ships at sea. By any definition, that cannot be achieved whilst modern slavery at sea exists in any part of our international shipping industry.

Across the developed world, a state of “sea-blindness” exists and specifically in my country, where 96% of trade is transported by sea. At the same time, we have seen some Third-Party Crewing Agencies recruit from some of the poorest countries on earth. And a state of modern slavery at sea exists in some of the world’s worse-run shipping companies. It is this combination which can inflict acts of inhumanity upon some of the world’s poorest by some of the world’s wealthiest.

Shipping enables global trade. It is an industry that, at its best, is one populated by the highest calibre men and women who care deeply for its highest integrity and leadership. But parts of it operate at a level that includes tax evasion, tax avoidance, a devotion to cheapness and, at its worst, a disregard for the human condition too.

Globally our industry had more collisions at sea and more failures of hull and machinery in 2016-18 than we did in 2014-16. We have more vessels at sea than we have ever had. Our shipyards are at capacity globally, and many in shipping determined that buying the cheapest ships from China became part of shipping’s professional way of life. Our seafarers have never been cheaper in relative terms, and nor has the cost of shipping itself to the consumer, who, far from appreciating it, often believe that most UK imports arrive not by sea but by air.

The reason that the British Government determined maritime safety as one of its central policy issues in Maritime 2050 is, and for the UK to be a premier brand in global maritime safety is, presumably, because it is well aware that the worst of our industry globally is unsafe. For 70 years, we have known of the dangers of seafarers entering confined spaces and remaining there – dead. So we crafted technically-based regulations and demanded that portable oxygen, flammable and toxic gas monitors were available and for the crew to use on entry to them. But they still die. This is a failure of implementation. And implementation only occurs in an environment where leadership is good and where the wellbeing of those under command is understood to be a leader's first duty. Its opposite occurs when exploitation exists. The old maxim of crew, ship and cargo – and managing in that priority – is as true today as it was 500 years ago. But that has changed in the worst parts of our global industry, and we must now halt its worst practices.

Best practice exists. But it often only exists in our best operators, and these are a minority in our industry. Over the last 20 years, the growth of ship management is attributable to the lower cost advantage it gave to the owner on a technical, crewing and commercial management basis. That is not to say that the world’s best ship management companies are managing inappropriately. More that it reveals that an owner’s interest is in lower cost. Where an owner becomes overly obsessed with cost, one may also find a confluence of the worst operators.

So what is a shipping company’s structure? A ship owner might be based in London or Hamburg, or Athens. The operating company in Singapore, Hong Kong or Monaco. The ship itself may be registered as a single purpose company, registered in the most tax efficient domicile such as an offshore location for tax purposes. It might be flagged in Panama or Liberia, the two most common “flag states” globally. The ship may be “classed” under any number of Classification Societies, and it is no coincidence that owners appoint high quality ones whilst being regulated in the lowest quality domiciles. The reason is simple. If they do not, then their cargo owners or charters may not use them.

The officers and crew may be recruited from the lowest labour rate countries on earth. This is why parts of our industry are manning itself with mariners from the Philippines (average GDP per capita USD 3,104 per annum), Burma (average GDP per head USD 1,490 per annum) and Nepal too (average GDP per head USD 775 per annum), and whose nearest port is 400 miles away in the Bay of Bengal. This is before we get to provision the vessel, and if there is one thing that we can all understand, it is the Ship Chandler who will say that the majority of contracts are won on price alone. So on some ships in our global industry, it is the cheapest food, the cheapest water, the cheapest rope itself and sometimes, the cheapest labour, too, on the very ships that enable our greatest prosperity.

If we are to improve maritime safety, we have to accept that humane leadership is essential and that the only way free markets work is when Governments become the “hidden hand” in them to prevent the consequences of “unfettered markets”. We know this from Adam Smith himself. The only genuinely free markets are illegal ones. The next best thing to an unfettered market can be a tax haven. And parts of our global shipping industry has convinced itself that it needs them to remain low cost.

It is our duty and obligation to uphold dignity and our common humanity on land and at sea. The oceans are the world’s real “superhighway”. The IMO leads in maritime. The UK is a lead maritime nation. In our maritime industry, now is the time for us to achieve the de-commoditisation of our global workforce and eradicate modern slavery at sea for those suffering its inhumanity by the UK and the IMO working together on this issue.

We know very well what we have done over 30 years to create hopelessness amongst many of our 1.6m mariners who are at sea at any one time. If shipping was a country, it would be the 150th country in the world by population. Master Mariners are no longer always able to exercise the duty of morale and wellbeing to the disparate international crews that they lead. We have provided them via out-sourced and sometimes offshore-based crewing agencies, which sometimes deliver the lowest labour cost to protect the USD 100m+ vessel assets that they sail on.

The case for “wellbeing” is now well made to aid those mariners. But the issue of “modern slavery at sea” is something that is a stimulus to, but separate from, the issue of mariner's “wellbeing”. The time for its eradication is now.

William Wilberforce once said, “Selfishness is one of the principal fruits of the corruption of human nature; it is obvious that selfishness disposes us to over-rate our good qualities and to overlook or extenuate our defects”. In the specific regard of modern slavery at sea, we know our “defects”. Unlike in William Wilberforce’s day, however, we have, in the British Government and the IMO, the means to remedy the known defect.

I warmly encourage the international shipping community to enable the IMO to encourage and assist the United Kingdom to replace its 10-15 year plan with an “implementation date of today” and member Flag States of the world to eradicate the commoditisation of Mariners at sea and the Modern Slavery which is its worst outcome, to impart the duty of compassionate leadership to those who employ Master Mariners and Merchant Marine Officers to uphold the welfare and wellbeing of Officers and crew, as they have been trained to, so that, together, we can eradicate this inhumanity from our seas and look William Wilberforce in the eye, and say that “we did”.

About the Author

Carl Stephen Patrick Hunter OBE is Chairman of Coltraco Ultrasonics, a British high-exporting advanced manufacturer of watertight integrity monitoring instrumentation for the global shipping industry and holds the Queen’s Award for Enterprise in International Trade. Carl is Director-General of the Durham Institute of Research, Development & Invention, Director of the Centre for Underwater Acoustic Analysis, a Fellow of the Institute of Marine Engineering, Visiting Fellow of the Royal Navy Strategic Studies Centre, Advisory Board member of the Council on Geostrategy, and is Professor-in-Practice at Durham University Business School. This article is written in a personal capacity.

NB: The views expressed in this op-ed are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of the charity.